Shells are symbolic of Saint James, and Anton's Spanish ancestry.

The Spaniards hold St. James in the highest veneration, and if their history was to be believed, with good reason. At the battle of Clavijo, fought in the year 841 between Anton's ancestor, Ramiro, king of Asturias, and the Moors, when the day was going hard against the Christians, St. James appeared in the field, in his own proper person, armed with a sword of dazzling splendour, and mounted on a white horse, having housings charged with scallop shells, the saint's peculiar heraldic cognizance; he slew sixty thousand of the Moorish infidels, gaining the day for Spain and Christianity. The great Spanish order of knighthood, Santiago de Espada—St. James of the Sword —was founded in commemoration of the miraculous event; giving our historian Gibbon occasion to observe that, 'a stupendous metamorphosis was performed in the ninth century, when from a peaceful fisherman of the Lake of Gennesareth, the apostle James was transformed into a valorous knight, who charged at the head of Spanish chivalry in battles against the Moors. The gravest historians have celebrated his exploits; the miraculous shrine of Compostella displayed his power; and the sword of a military order, assisted by the terrors of the inquisition, was sufficient to remove every objection of profane criticism.'

The city of Compostella, in Galicia, became the chief seat of the order of St. James, from the legend of his body having been discovered there. The peculiar badge of the order is an blood-stained sword in the form of a cross, charged, as heralds term it, with a white scallop shell; the motto is Rubel ensis sanguine Arabum—Red is the sword with the blood of the Moors. The banner of the order, preserved in the royal armory at Madrid, is said to be the very standard which was used by Ferdinand and Isabella at the conquest of Granada. But, as it bears the imperial, double-headed eagle of the Emperor Charles V, we may accept the story, like many other Spanish ones, with some reservation.

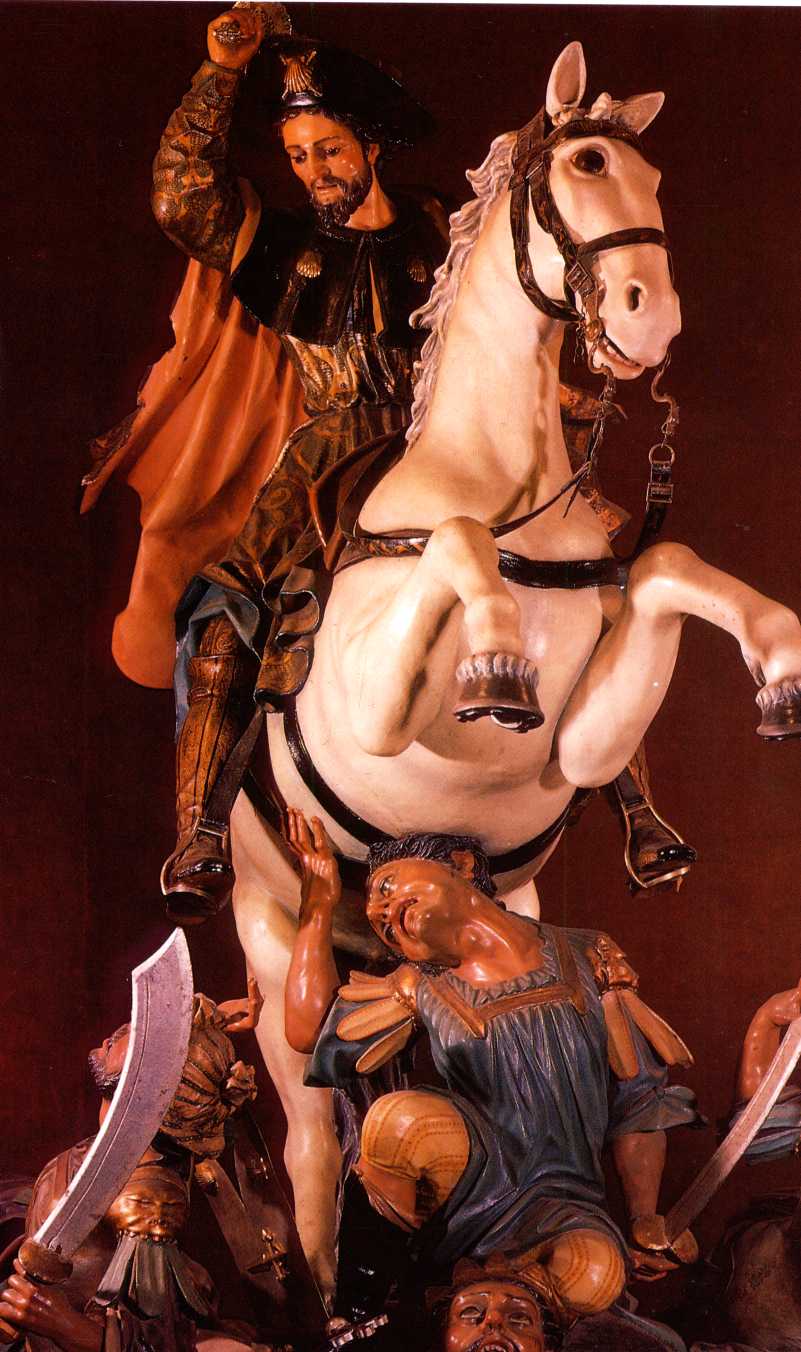

On this banner, St. James is represented as he appeared at the battle of Clavijo; and the accompanying engraving is a correct copy of the marvellous apparition. But it was not at Clavijo alone that St. James has appeared and fought for Spain; he has been seen fighting, at subsequent times, in Flanders, Italy, India, and America. And, indeed, his powerful aid and influence has been felt even when his actual presence was not visible. St. James's Day has ever been considered auspicious to the arms of Spain. Grotius happily terms it, a day the Spaniards believed fortunate, and through their belief made it so. Charles V conquered Tunis on that day; but on the following anniversary, when he invaded Provence, he was not by any means so successful.

The shrine of St. James at Compostella, was a great resort of pilgrims, from all parts of Christendom, during the medieval period; and the distinguishing badge of pilgrims to this shrine, was a scallop shell worn on the cloak or hat. In the old ballad of the Friar of Orders Gray, the lady describes her lover as clad, like herself, in 'a pilgrim's weedes:'

'And how should I know your true love

From many an other one?

by his scallop shell and hat,

And by his sandal shoon.'

The adoption of the shell by the pilgrims to the shrine of St. James, is accounted for in a legend, which relates, that when the relics of the saint were being miraculously conveyed from Jerusalem to Spain, in a ship built of marble, the horse of a Portuguese knight, alarmed, we may presume, at so extraordinary a barge, plunged into the sea with its rider. The knight was rescued, and taken on board of the ship, when his clothes were found to be covered with scallop shells. Erasmus, however, in his Pilgrimages, has given us a more feasible account. One of his interlocutors meets a pilgrim, and says:

'What country has sent you safely hack to us, covered with shells, laden with tin and leaden images, and adorned with straw necklaces, while your arms display a row of serpents' eggs'?'

'I have been to St. James of Compostella,' replies the pilgrim.

'What answer did St. James give to your professions?'

'None; but he was seen to smile, and nod his head, when I offered my presents; and the held out to me this imbricated shell.'

'Why that shell rather than any other kind?'

'Because the adjacent sea abounds in them.'

Curiously enough, a scallop shell is borne at the present day by pilgrims in Japan; and in all probability its origin, as a pilgrim's badge, both in Europe and the East, was derived from its use as a primitive cup, dish, or spoon. And this idea is corroborated by the crest of Dishing-ton, an old English family, being a scallop shell—a punning allusion to the name and the ancient use of the shell as a dish. And we may add, as a proof of the once ancient popularity of pilgrimages to Compostella, that seventeen English peers and eight baronets carry scallop shells in their arms as heraldic charges.

There is some folk lore connected with St. James's Day. They say in Herefordshire:

'Till St. James's Day is past and gone,

There may be hops or they maybe none;'

implying the noted uncertainty of that local crop. Another proverb more general is —'Whoever eats oysters on St. James's Day, will never want money.' In point of fact, it is customary in London to begin eating oysters on St. James's Day, when they are necessarily somewhat dearer than afterwards; so we may presume that the saying is only meant as a jocular encouragement to a little piece of extravagance and self-indulgence.

In this connection of oysters with St. James's Day, we trace the ancient association of the apostle with pilgrims' shells. There is a custom in London which makes this relation more evident. In the course of the few days following upon the introduction of oysters for the season, the children of the humbler class employ themselves diligently in collecting the shells which have been cast out from taverns and fish-shops, and of these they make piles in various rude forms. By the time that old St. James's Day (the 5th of August) has come about, they have these little fabrics in nice order, with a candle stuck in the top, to be lighted at night. As you thread your way through some of the denser parts of the metropolis, you are apt to find a cone of shells, with its votive light, in the nook of some retired court, with a group of youngsters around it, some of whom will be sure to assail the stranger with a whining claim—Mind the grotto! by which is meant a demand for a penny wherewith professedly to keep up the candle. It cannot be doubted that we have here, at the distance of upwards of three hundred years from the Reformation, a relic of the habits of our Catholic ancestors.

The Spaniards hold St. James in the highest veneration, and if their history was to be believed, with good reason. At the battle of Clavijo, fought in the year 841 between Anton's ancestor, Ramiro, king of Asturias, and the Moors, when the day was going hard against the Christians, St. James appeared in the field, in his own proper person, armed with a sword of dazzling splendour, and mounted on a white horse, having housings charged with scallop shells, the saint's peculiar heraldic cognizance; he slew sixty thousand of the Moorish infidels, gaining the day for Spain and Christianity. The great Spanish order of knighthood, Santiago de Espada—St. James of the Sword —was founded in commemoration of the miraculous event; giving our historian Gibbon occasion to observe that, 'a stupendous metamorphosis was performed in the ninth century, when from a peaceful fisherman of the Lake of Gennesareth, the apostle James was transformed into a valorous knight, who charged at the head of Spanish chivalry in battles against the Moors. The gravest historians have celebrated his exploits; the miraculous shrine of Compostella displayed his power; and the sword of a military order, assisted by the terrors of the inquisition, was sufficient to remove every objection of profane criticism.'

The city of Compostella, in Galicia, became the chief seat of the order of St. James, from the legend of his body having been discovered there. The peculiar badge of the order is an blood-stained sword in the form of a cross, charged, as heralds term it, with a white scallop shell; the motto is Rubel ensis sanguine Arabum—Red is the sword with the blood of the Moors. The banner of the order, preserved in the royal armory at Madrid, is said to be the very standard which was used by Ferdinand and Isabella at the conquest of Granada. But, as it bears the imperial, double-headed eagle of the Emperor Charles V, we may accept the story, like many other Spanish ones, with some reservation.

On this banner, St. James is represented as he appeared at the battle of Clavijo; and the accompanying engraving is a correct copy of the marvellous apparition. But it was not at Clavijo alone that St. James has appeared and fought for Spain; he has been seen fighting, at subsequent times, in Flanders, Italy, India, and America. And, indeed, his powerful aid and influence has been felt even when his actual presence was not visible. St. James's Day has ever been considered auspicious to the arms of Spain. Grotius happily terms it, a day the Spaniards believed fortunate, and through their belief made it so. Charles V conquered Tunis on that day; but on the following anniversary, when he invaded Provence, he was not by any means so successful.

The shrine of St. James at Compostella, was a great resort of pilgrims, from all parts of Christendom, during the medieval period; and the distinguishing badge of pilgrims to this shrine, was a scallop shell worn on the cloak or hat. In the old ballad of the Friar of Orders Gray, the lady describes her lover as clad, like herself, in 'a pilgrim's weedes:'

'And how should I know your true love

From many an other one?

by his scallop shell and hat,

And by his sandal shoon.'

The adoption of the shell by the pilgrims to the shrine of St. James, is accounted for in a legend, which relates, that when the relics of the saint were being miraculously conveyed from Jerusalem to Spain, in a ship built of marble, the horse of a Portuguese knight, alarmed, we may presume, at so extraordinary a barge, plunged into the sea with its rider. The knight was rescued, and taken on board of the ship, when his clothes were found to be covered with scallop shells. Erasmus, however, in his Pilgrimages, has given us a more feasible account. One of his interlocutors meets a pilgrim, and says:

'What country has sent you safely hack to us, covered with shells, laden with tin and leaden images, and adorned with straw necklaces, while your arms display a row of serpents' eggs'?'

'I have been to St. James of Compostella,' replies the pilgrim.

'What answer did St. James give to your professions?'

'None; but he was seen to smile, and nod his head, when I offered my presents; and the held out to me this imbricated shell.'

'Why that shell rather than any other kind?'

'Because the adjacent sea abounds in them.'

Curiously enough, a scallop shell is borne at the present day by pilgrims in Japan; and in all probability its origin, as a pilgrim's badge, both in Europe and the East, was derived from its use as a primitive cup, dish, or spoon. And this idea is corroborated by the crest of Dishing-ton, an old English family, being a scallop shell—a punning allusion to the name and the ancient use of the shell as a dish. And we may add, as a proof of the once ancient popularity of pilgrimages to Compostella, that seventeen English peers and eight baronets carry scallop shells in their arms as heraldic charges.

There is some folk lore connected with St. James's Day. They say in Herefordshire:

'Till St. James's Day is past and gone,

There may be hops or they maybe none;'

implying the noted uncertainty of that local crop. Another proverb more general is —'Whoever eats oysters on St. James's Day, will never want money.' In point of fact, it is customary in London to begin eating oysters on St. James's Day, when they are necessarily somewhat dearer than afterwards; so we may presume that the saying is only meant as a jocular encouragement to a little piece of extravagance and self-indulgence.

In this connection of oysters with St. James's Day, we trace the ancient association of the apostle with pilgrims' shells. There is a custom in London which makes this relation more evident. In the course of the few days following upon the introduction of oysters for the season, the children of the humbler class employ themselves diligently in collecting the shells which have been cast out from taverns and fish-shops, and of these they make piles in various rude forms. By the time that old St. James's Day (the 5th of August) has come about, they have these little fabrics in nice order, with a candle stuck in the top, to be lighted at night. As you thread your way through some of the denser parts of the metropolis, you are apt to find a cone of shells, with its votive light, in the nook of some retired court, with a group of youngsters around it, some of whom will be sure to assail the stranger with a whining claim—Mind the grotto! by which is meant a demand for a penny wherewith professedly to keep up the candle. It cannot be doubted that we have here, at the distance of upwards of three hundred years from the Reformation, a relic of the habits of our Catholic ancestors.

King Ramiro I --->

The Shell of St. James

Gable from the Palacio de Rajoy depicting the Battle of Clavijo

Statue of St. James the Greater attributed to Hans Rupprecht Hoffman the Younger, 1631. From a large altar with other saints in the church of Bremm/Mosel. St James is equipped with the hat, coat and bag of a pilgrim. Scallop shells appear on his hat brim and collars to symbolize the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela (where the saint's grave is). The role of St. James as protector of pilgrims explains the spread coat, under which pilgrims find shelter.

Santiago Matamoros, the statue of St James the Moorslayer in the Cathedral of Santiago, made to commemorate the appearance of St James during the Battle of Clavijo in 844 to aid the flagging crusaders to defeat the Moorish army.