Ghellinges / Gilling North Yorkshire

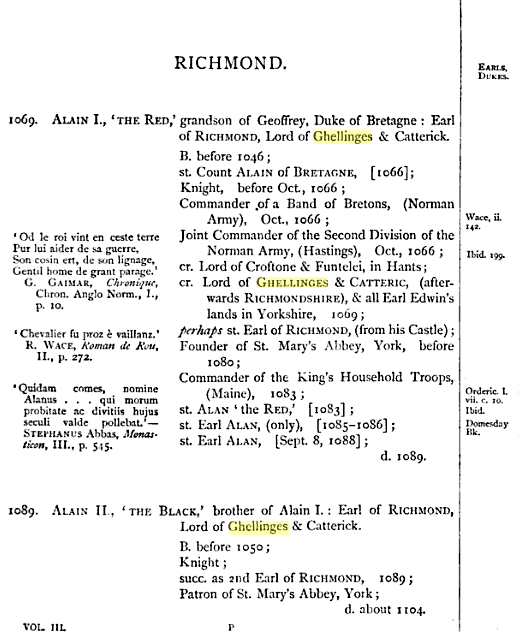

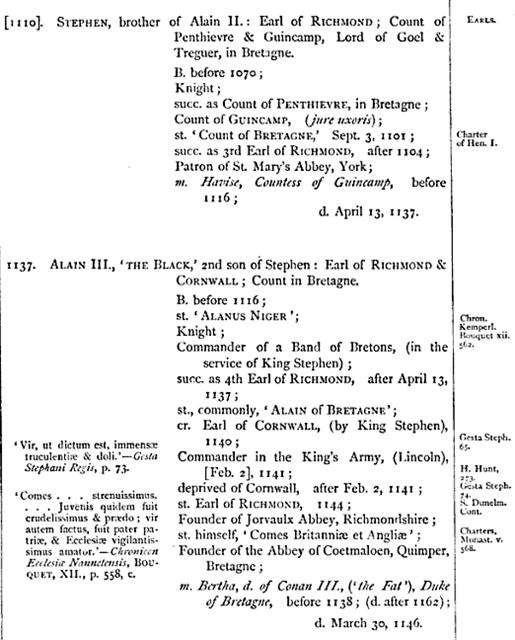

Anton is descended from the ancient Lords of Ghellinges (today called Gilling) where Hartforth is located.

Anton is descended from the ancient Lords of Ghellinges (today called Gilling) where Hartforth is located.

Gilling was once a place of considerable importance, in the 7th century being a principal seat of the Kings of Deira, the southern part of the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria.

From the 9th century Gillingshire was ruled by the Earls of Mercia, the last of whom, Edwin,had his stronghold on Castle Hill near to where Low Scales Farm now stands. However the Norman Conquest brought many changes and William gave Edwin's lands to his kinsman Alan Rufus, who built his mighty castle several miles away in Richmond - this led towards the demise of Gilling's former high status in the area.

The Domesday Book records that a Church existed in Gilling (Ghellinges) in the year 1086 and it has long been thought that the present church arose on the site of a monastery destroyed by the Danes. The Church was either restored or rebuilt about the end of the 11th century with additions in the 14th century, Many major alterations were carried out in 1845.

MONASTIC GILLlNG

The beginnings of Christianity in what is now Yorkshire but was once the Anglian kingdom of Deira (from time to time joined with its northern neighbour Bernicia to form Northumbria) may be traced back as far-as AD. 314, when a bishop of York is mentioned as being present at the Coiuncil of Arles. After the Saxon invasions of Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries the flame of faith in the north was rekindled when Edwin, king of Northumbria, married the Christian Ethelburga of Kent, and one of Augustine's fellow-missionaries, Paulinus, was consecrated bishop of York. This was in 625, twenty-eight years after Augustine had established the English church at Canterbury. It was Paulinus of whom Bede wrote: '….he baptised in the river Swale, which runs by the village of Cataract (Catterick)' - the earliest specific reference to Christianity in the neighbourhood of Gilling (The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (1910).

When Edwin was defeated in 633 Paulinus escaped to Kent, taking with him Edwin's widow and her daughter Eanfleda. A year later Oswald, Edwin's nephew, routed the pagan British at Heavenfield, near Hexham, and the northern kingdom was again brought under Christian rule. Oswald had been converted by the monks of Iona, and it was in response to an appeal from him that Aidan was sent to be bishop of Lindisfarne, 'to preach to the Northumbrians'. But when Oswald himself was killed, in 642, his realm was divided. Oswi, his younger brother and husband of Eanfleda, succeeded in Bernicia, while Deira acknowledged Oswin. Nine years later Oswi laid claim to the whole of Northumbria, and a battle was imminent; but Oswin, seeing the strength of Oswi's forces, dismissed his men 'at the place which is called Wilfaresdun, that is, Wilfar's Hill, which is almost ten miles distant from the village called Cataract, towards the north-west'. He concealed himself in the house of a supposed friend, but was betrayed and then murdered on Oswi's orders. This happened, Bede continues, on August 20th, 651, 'at a place called Ingethlingum, where afterwards a monastery was built'. Oswi granted the monastery site in response to Eanfleda's entreaty and 'in satisfaction for Oswin's unjust death'.

Where was Ingethlingum? Geographical and etymological consideration led T.D.Whitaker (History of Richmondshire (1823)) and earlier historians to accept Gilling as the scene of Oswin's death and the site of the monastery. But in 1870 D. H. Haigh published a paper, The Runic Monuments of Northumbria, in which he argued that the more likely location was Collingham, near Wetherby. His view was based on his interpretation of some very indistinct runic markings on a monumental stone that had been disinterred near the foundations of Collingham church in 1841. Haigh first saw the stone in 1855 when, he said, 'I read quite plainly…..the name Auswini', and there were faint traces of other words. Returning in 1870 he found the marks 'not nearly as plain'; nevertheless with the aid of casts and photographs he attempted a restoration of the whole inscription, as follows: 'Aeonblaed this set / After (her) cousin / After Oswini (the) king / Pray for the soul'. The name Aeonblaed he took to be an earlier form of Eanfleda. In spite of the highly speculative nature of Haigh's work, his paper led writers such as Harry Speight (Romantic Richmondshire (1897), Edmund Bogg (Richmondshire (1908)), and even the compilers of the Victoria History of the North Riding (1914), to abandon the belief that Bede's reference was to Gilling. But in 1915 W.G.Collingwood, a considerable authority on Anglo-Danish monuments, categorically rejected the Collingham theory. 'It is certain', he said, 'that the name on the stone is not Oswini, and it is evident that the date of the design is much later than the seventh century'. This opinion received powerful support from T.D. Kendrick, Keeper of British Antiquities in the British Museum, in his book Anglo-Saxon Art (1938), where he cites the Collingham stone as a particularly good example of 9th century work. Nikolaus Pevsner (Yorkshire - The West Riding (1967)) concurs, and it being manifestly impossible for a 7th century queen to have set up a 9th century stone, we may well agree with Ekwall (English Place Names, 1959 edn.) when he writes: 'With Gilling near Richmond is usually and no doubt correctly identified Ingethlingum'.

Bede tells us that the first abbot of the monastery at Ingethlingum was Trumhere, a Northumbrian priest who in 659 was made bishop of the Mercians. One of Bede's sources for his Lives of the Holy Abbots was a work known as The Anonymous Life of Ceolfrith, Abbot of Jarrow, which had been written after Ceolfrith's death. Although the author is unknown his text survives, and a single sentence throws light on Gilling history: 'When he Ceolfrith had almost reached the eighteenth year of his age he entered the monastery situated in the place which is called Ingethlingum….which his brother Cynefrith... had ruled... but had committed shortly before to the rule of his kinsman Tunberht'. Ceolfrith, according to Bede, died in 716 at the age of 74, which sets the year of his arrival in Gilling at 660. We may thus suppose that the Gilling monastery was built very soon after 651; that Trumhere was followed in 659 by Cynefrith; and that about a year later Tunberht succeeded him. These three are the only abbots of whom we have any record, although the building itself may have stood for another two hundred years, until the wholesale destruction of religious houses in the Danish invasions of 866-7.

Not a trace of this monastery remains today, but fragments of Anglo-Saxon sculptured crosses displayed in the church porch testify to the survival of Christian worship in Gilling in the 9th and 10th centuries. A very common form of Anglian monument was a cross head crowning a square shaft decorated with scrolls showing fruits or foliage, sometimes with birds or other small creatures among the branches. Danish crosses on the other hand often had wheel heads, and the sculpture was rougher and less naturalistic, with decoration resembling interlacing ropework. Collingwood has described the Gilling stones in some detail. They include one 9th century cross head (late Anglian) on which a superimposed 'lorgnette' cross has round terminals representing the rivets of earlier applied metalwork crosses. Two other fragments are typical Norse wheel heads, one with a lorgnette, the other with rope tracery. There are also two pieces of shaft from the Viking age, both decorated with ropework. One of these, sixteen inches high, has a tapering rectangular column rising from a cylindrical base. The second, ten inches taller, shows on one side the body and tail of a ribbon-beast and may originally have been part of a monument twelve feet high. All the pieces are of brown sandstone, and much defaced. A large flat stone lying in the turf opposite the church porch (and now surmounted by three other blocks) may have been a cross base.

Two or three of these stones were dug out when a cellar was being made at Waterloo House, next to the Post Office. There are other indications that a considerable area of land lying south and east of the present church was once an ecclesiastical site. John Shaw, a native of Gilling, writing in 1867, mentioned the discovery of many human bones when the house adjoining the 'White Swan' on the south was built about fifty years before; and he continued: 'A new end was added to the house a few years ago, when more human bones were found; and in the garth behind and I think also in Mr Wharton's garden in digging post holes many human bones were found'. We have no means of dating these remains, but the probability that this was a burial ground is suggestive, since sites once consecrated usually persist over long periods, Shaw also stated that the 'Angel' inn was formerly a religious house - 'there has been many little windows and arches in it not visible now' - and H. A. Morrison, vicar from 1961 to 1967, drew attention to the adjoining cottages which, he suggested, still preserve traces of a mediaeval foundation, perhaps the chapel of a post-Conquest nunnery or monastery. There is a blocked square window in the south wall, and below it to the right what seems to be the remains of the arch of a doorway, though much of the latter was hidden when the cottages were converted to a single dwelling in 1963. The position of the arch, near to the ground, indicates that the building used to stand much further above ground level. The wide round arch of another doorway appears low in the east wall of the house and above are two blocked windows with arches similar in design to the others. If indeed a chapel once stood here, Morrison said, the east windows would have been above the altar and the arch below them would have represented the entry from the religious house. The doorway in the south wall would be in the correct position for a public entrance to the chapel. Only perhaps by stripping the inner face of the east wall back to the original stone could further evidence of the history of this building be obtained.

The years following Oswi's death in 670 were a high tide in the history of the English church, and nowhere more than in Northumbria - where Hilda ruled, Cuthbert preached and Bede wrote. Although the tide receded, and reached its lowest ebb at the close of the 9th century, yet an organisation had been established which was to survive the razing of buildings. By the 11th century the Danes had been largely absorbed and churches were again being built of restored. The tower of Gilling church may possibly retain traces of Saxon work - large irregular corner stones in the lowest courses, relatively thin walls, and perhaps even the jambs and arches of the blocked windows of the old belfry - but it is essentially Norman. In 1086 the church "in Ghellinges" was recorded in Domesday Book.

THE MANOR AND PARISH OF GILLlNG

Already in the 7th century Gilling was one of the principal seats of the kings of Deira, and in the 10th it gave its name to one of the largest of the wapentakes into which the Riding was divided by the Danish invaders. It became the administrative centre for all the land between the Swale and the Tees, from the river Wiske to Westmorland. From the 9th century Gillingshire was held by the earls of Mercia, the last of whom, Edwin, may have had his manor house on Castle Hill, three hundred yards north-west of where Low Scales farm now stands. The site name is very old: a register book of St. Mary's abbey at York gives particulars of lands in 1309 'the tithes whereof appertain to the church of Gillyng', listing among other items 'three roods at Castle Hill' and 'one acre upon Castle Hill'. Writing in 1823 Whitaker stated that 'the last vestiges of Gilling Castle, the seat of the Saxon earls, are well remembered and were lately removed from the summit of the hill about a mile south of Gilling church'. Twenty-six years later Henry Maclauchlan (The Archeological Journal, Volume 6) found difficulty in identifying the precise location but talked with two old labourers, John Alien and Jenny Feetham (she born in 1750), who recalled helping to break up the foundations of the building, the walls of which had been four feet thick.

The manor of Gilling formed part of the vast possessions given by the Conqueror to his kinsman and supporter Alan Rufus, who built Richmond Castle. Edwin's house would be a wooden structure, which Alan may have rebuilt in stone pending the completion of his new fortress on the Swale. The importance of Gilling rapidly declined and apart from the somewhat scant records of landed families associated with the parish knowledge of its subsequent history centres almost entirely on the church. Rare indeed are such personal recollections as the following extract from John Warburton's diary written in the early 18th century: 'Thursday, October 16. Went from Walburn Hall to Richmond, about two miles of moorish ground and bad way, and thence to Ask Hall - belonging to His Grace the Duke of Wharton, to Gilling, a large church town, standing in a vally, not far from which is Sadbery, the seat of (James) Darcy, Esq., and Gillingwood, of (William) Wharton, Esq. Lodgd all night with Mr Matt. Smailes, an attorney-at-law in the town.'

We do not know just how much Gilling suffered in that 'harrying of the north' which in 1069 laid waste most of Northumbria - William the First's fearful answer to those who had resisted him; but even seventeen years afterwards only four ploughs were at work there on land sufficient for sixteen. Nevertheless the church was almost entirely rebuilt soon afterwards; the corners of the present nave and most of the tower date from that period. Before the 11th century closed it was given to the newly-founded abbey of St. Mary's in York, to which the tithes and other endowments were appropriated in 1224. The advowson (the right of presentation of incumbents) remained with the abbey until the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. St. Mary's became one of the largest and wealthiest of the Benedictine houses, holding manors and churches in many parts of Yorkshire. The abbey ruins may still be seen, the grounds forming a splendid setting for the Yorkshire Museum. This museum, incidentally, now displays the Gilling Sword, a fine Anglo-Saxon weapon 32.5 inches long, with its blade largely intact and with five silver bands around the hilt. The sword was found near the old ford at Gilling bridge in 1976, doubtless having been dredged up from its peat bed during re-grading of the beck.

In mediaeval times, and until comparatively recently, the parish of Gilling extended far beyond its present boundaries. In 1233 the Pope licensed the archbishop of York to build chapels in outlying places to be served by curates paid by the vicar. The necessity for such 'chapels of ease' was especially felt in Yorkshire, where a great many people might be cut off from their parish church in winter by flooded rivers and impassable roads. The archives of the see of York show that in 1344 'the abbey of St. Mary's possessed the church of Gilling with the chapels dependent thereon', and the abbey register for 1309 gives those chapels as Barton St. Mary's, Eriom (Eryholme), Cowton, Forcett, Hutton Magna, Appleby-on-Tees (Eppleby), Barford-on-Tees and Mortham. Already in the 15th century Mortham lay waste, and St. Lawrence, Barford, just south of Gainford, has long been a total ruin, but a report of the Charity Commissioners in 1548 in respect of Gilling could still speak of 'six prestes belonging to the sayd paryshe at the findyng of the vacare there, besides the two chauntrye prestes'. Parish returns in 1783 and later years show 'annual immemorial payments' made out of the vicar's income to the curates of Forcett, Hutton Magna, Barton St. Mary's and Cowton. These places, with Eppleby, Eryholme and parts of Stapleton, are marked 'Gilling (detached)' on the first of the six-inch Ordnance Survey maps of the district, published in 1857. But although the vicar of Gilling is still a patron of the churches at Hutton Magna, South Cowton and Eryholme, all dependent chapelries of the ancient parish were designated vicarages by the late 19th century, having been declared independent benefices following the Pluralities Act of 1838.

From the 9th century Gillingshire was ruled by the Earls of Mercia, the last of whom, Edwin,had his stronghold on Castle Hill near to where Low Scales Farm now stands. However the Norman Conquest brought many changes and William gave Edwin's lands to his kinsman Alan Rufus, who built his mighty castle several miles away in Richmond - this led towards the demise of Gilling's former high status in the area.

The Domesday Book records that a Church existed in Gilling (Ghellinges) in the year 1086 and it has long been thought that the present church arose on the site of a monastery destroyed by the Danes. The Church was either restored or rebuilt about the end of the 11th century with additions in the 14th century, Many major alterations were carried out in 1845.

MONASTIC GILLlNG

The beginnings of Christianity in what is now Yorkshire but was once the Anglian kingdom of Deira (from time to time joined with its northern neighbour Bernicia to form Northumbria) may be traced back as far-as AD. 314, when a bishop of York is mentioned as being present at the Coiuncil of Arles. After the Saxon invasions of Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries the flame of faith in the north was rekindled when Edwin, king of Northumbria, married the Christian Ethelburga of Kent, and one of Augustine's fellow-missionaries, Paulinus, was consecrated bishop of York. This was in 625, twenty-eight years after Augustine had established the English church at Canterbury. It was Paulinus of whom Bede wrote: '….he baptised in the river Swale, which runs by the village of Cataract (Catterick)' - the earliest specific reference to Christianity in the neighbourhood of Gilling (The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (1910).

When Edwin was defeated in 633 Paulinus escaped to Kent, taking with him Edwin's widow and her daughter Eanfleda. A year later Oswald, Edwin's nephew, routed the pagan British at Heavenfield, near Hexham, and the northern kingdom was again brought under Christian rule. Oswald had been converted by the monks of Iona, and it was in response to an appeal from him that Aidan was sent to be bishop of Lindisfarne, 'to preach to the Northumbrians'. But when Oswald himself was killed, in 642, his realm was divided. Oswi, his younger brother and husband of Eanfleda, succeeded in Bernicia, while Deira acknowledged Oswin. Nine years later Oswi laid claim to the whole of Northumbria, and a battle was imminent; but Oswin, seeing the strength of Oswi's forces, dismissed his men 'at the place which is called Wilfaresdun, that is, Wilfar's Hill, which is almost ten miles distant from the village called Cataract, towards the north-west'. He concealed himself in the house of a supposed friend, but was betrayed and then murdered on Oswi's orders. This happened, Bede continues, on August 20th, 651, 'at a place called Ingethlingum, where afterwards a monastery was built'. Oswi granted the monastery site in response to Eanfleda's entreaty and 'in satisfaction for Oswin's unjust death'.

Where was Ingethlingum? Geographical and etymological consideration led T.D.Whitaker (History of Richmondshire (1823)) and earlier historians to accept Gilling as the scene of Oswin's death and the site of the monastery. But in 1870 D. H. Haigh published a paper, The Runic Monuments of Northumbria, in which he argued that the more likely location was Collingham, near Wetherby. His view was based on his interpretation of some very indistinct runic markings on a monumental stone that had been disinterred near the foundations of Collingham church in 1841. Haigh first saw the stone in 1855 when, he said, 'I read quite plainly…..the name Auswini', and there were faint traces of other words. Returning in 1870 he found the marks 'not nearly as plain'; nevertheless with the aid of casts and photographs he attempted a restoration of the whole inscription, as follows: 'Aeonblaed this set / After (her) cousin / After Oswini (the) king / Pray for the soul'. The name Aeonblaed he took to be an earlier form of Eanfleda. In spite of the highly speculative nature of Haigh's work, his paper led writers such as Harry Speight (Romantic Richmondshire (1897), Edmund Bogg (Richmondshire (1908)), and even the compilers of the Victoria History of the North Riding (1914), to abandon the belief that Bede's reference was to Gilling. But in 1915 W.G.Collingwood, a considerable authority on Anglo-Danish monuments, categorically rejected the Collingham theory. 'It is certain', he said, 'that the name on the stone is not Oswini, and it is evident that the date of the design is much later than the seventh century'. This opinion received powerful support from T.D. Kendrick, Keeper of British Antiquities in the British Museum, in his book Anglo-Saxon Art (1938), where he cites the Collingham stone as a particularly good example of 9th century work. Nikolaus Pevsner (Yorkshire - The West Riding (1967)) concurs, and it being manifestly impossible for a 7th century queen to have set up a 9th century stone, we may well agree with Ekwall (English Place Names, 1959 edn.) when he writes: 'With Gilling near Richmond is usually and no doubt correctly identified Ingethlingum'.

Bede tells us that the first abbot of the monastery at Ingethlingum was Trumhere, a Northumbrian priest who in 659 was made bishop of the Mercians. One of Bede's sources for his Lives of the Holy Abbots was a work known as The Anonymous Life of Ceolfrith, Abbot of Jarrow, which had been written after Ceolfrith's death. Although the author is unknown his text survives, and a single sentence throws light on Gilling history: 'When he Ceolfrith had almost reached the eighteenth year of his age he entered the monastery situated in the place which is called Ingethlingum….which his brother Cynefrith... had ruled... but had committed shortly before to the rule of his kinsman Tunberht'. Ceolfrith, according to Bede, died in 716 at the age of 74, which sets the year of his arrival in Gilling at 660. We may thus suppose that the Gilling monastery was built very soon after 651; that Trumhere was followed in 659 by Cynefrith; and that about a year later Tunberht succeeded him. These three are the only abbots of whom we have any record, although the building itself may have stood for another two hundred years, until the wholesale destruction of religious houses in the Danish invasions of 866-7.

Not a trace of this monastery remains today, but fragments of Anglo-Saxon sculptured crosses displayed in the church porch testify to the survival of Christian worship in Gilling in the 9th and 10th centuries. A very common form of Anglian monument was a cross head crowning a square shaft decorated with scrolls showing fruits or foliage, sometimes with birds or other small creatures among the branches. Danish crosses on the other hand often had wheel heads, and the sculpture was rougher and less naturalistic, with decoration resembling interlacing ropework. Collingwood has described the Gilling stones in some detail. They include one 9th century cross head (late Anglian) on which a superimposed 'lorgnette' cross has round terminals representing the rivets of earlier applied metalwork crosses. Two other fragments are typical Norse wheel heads, one with a lorgnette, the other with rope tracery. There are also two pieces of shaft from the Viking age, both decorated with ropework. One of these, sixteen inches high, has a tapering rectangular column rising from a cylindrical base. The second, ten inches taller, shows on one side the body and tail of a ribbon-beast and may originally have been part of a monument twelve feet high. All the pieces are of brown sandstone, and much defaced. A large flat stone lying in the turf opposite the church porch (and now surmounted by three other blocks) may have been a cross base.

Two or three of these stones were dug out when a cellar was being made at Waterloo House, next to the Post Office. There are other indications that a considerable area of land lying south and east of the present church was once an ecclesiastical site. John Shaw, a native of Gilling, writing in 1867, mentioned the discovery of many human bones when the house adjoining the 'White Swan' on the south was built about fifty years before; and he continued: 'A new end was added to the house a few years ago, when more human bones were found; and in the garth behind and I think also in Mr Wharton's garden in digging post holes many human bones were found'. We have no means of dating these remains, but the probability that this was a burial ground is suggestive, since sites once consecrated usually persist over long periods, Shaw also stated that the 'Angel' inn was formerly a religious house - 'there has been many little windows and arches in it not visible now' - and H. A. Morrison, vicar from 1961 to 1967, drew attention to the adjoining cottages which, he suggested, still preserve traces of a mediaeval foundation, perhaps the chapel of a post-Conquest nunnery or monastery. There is a blocked square window in the south wall, and below it to the right what seems to be the remains of the arch of a doorway, though much of the latter was hidden when the cottages were converted to a single dwelling in 1963. The position of the arch, near to the ground, indicates that the building used to stand much further above ground level. The wide round arch of another doorway appears low in the east wall of the house and above are two blocked windows with arches similar in design to the others. If indeed a chapel once stood here, Morrison said, the east windows would have been above the altar and the arch below them would have represented the entry from the religious house. The doorway in the south wall would be in the correct position for a public entrance to the chapel. Only perhaps by stripping the inner face of the east wall back to the original stone could further evidence of the history of this building be obtained.

The years following Oswi's death in 670 were a high tide in the history of the English church, and nowhere more than in Northumbria - where Hilda ruled, Cuthbert preached and Bede wrote. Although the tide receded, and reached its lowest ebb at the close of the 9th century, yet an organisation had been established which was to survive the razing of buildings. By the 11th century the Danes had been largely absorbed and churches were again being built of restored. The tower of Gilling church may possibly retain traces of Saxon work - large irregular corner stones in the lowest courses, relatively thin walls, and perhaps even the jambs and arches of the blocked windows of the old belfry - but it is essentially Norman. In 1086 the church "in Ghellinges" was recorded in Domesday Book.

THE MANOR AND PARISH OF GILLlNG

Already in the 7th century Gilling was one of the principal seats of the kings of Deira, and in the 10th it gave its name to one of the largest of the wapentakes into which the Riding was divided by the Danish invaders. It became the administrative centre for all the land between the Swale and the Tees, from the river Wiske to Westmorland. From the 9th century Gillingshire was held by the earls of Mercia, the last of whom, Edwin, may have had his manor house on Castle Hill, three hundred yards north-west of where Low Scales farm now stands. The site name is very old: a register book of St. Mary's abbey at York gives particulars of lands in 1309 'the tithes whereof appertain to the church of Gillyng', listing among other items 'three roods at Castle Hill' and 'one acre upon Castle Hill'. Writing in 1823 Whitaker stated that 'the last vestiges of Gilling Castle, the seat of the Saxon earls, are well remembered and were lately removed from the summit of the hill about a mile south of Gilling church'. Twenty-six years later Henry Maclauchlan (The Archeological Journal, Volume 6) found difficulty in identifying the precise location but talked with two old labourers, John Alien and Jenny Feetham (she born in 1750), who recalled helping to break up the foundations of the building, the walls of which had been four feet thick.

The manor of Gilling formed part of the vast possessions given by the Conqueror to his kinsman and supporter Alan Rufus, who built Richmond Castle. Edwin's house would be a wooden structure, which Alan may have rebuilt in stone pending the completion of his new fortress on the Swale. The importance of Gilling rapidly declined and apart from the somewhat scant records of landed families associated with the parish knowledge of its subsequent history centres almost entirely on the church. Rare indeed are such personal recollections as the following extract from John Warburton's diary written in the early 18th century: 'Thursday, October 16. Went from Walburn Hall to Richmond, about two miles of moorish ground and bad way, and thence to Ask Hall - belonging to His Grace the Duke of Wharton, to Gilling, a large church town, standing in a vally, not far from which is Sadbery, the seat of (James) Darcy, Esq., and Gillingwood, of (William) Wharton, Esq. Lodgd all night with Mr Matt. Smailes, an attorney-at-law in the town.'

We do not know just how much Gilling suffered in that 'harrying of the north' which in 1069 laid waste most of Northumbria - William the First's fearful answer to those who had resisted him; but even seventeen years afterwards only four ploughs were at work there on land sufficient for sixteen. Nevertheless the church was almost entirely rebuilt soon afterwards; the corners of the present nave and most of the tower date from that period. Before the 11th century closed it was given to the newly-founded abbey of St. Mary's in York, to which the tithes and other endowments were appropriated in 1224. The advowson (the right of presentation of incumbents) remained with the abbey until the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. St. Mary's became one of the largest and wealthiest of the Benedictine houses, holding manors and churches in many parts of Yorkshire. The abbey ruins may still be seen, the grounds forming a splendid setting for the Yorkshire Museum. This museum, incidentally, now displays the Gilling Sword, a fine Anglo-Saxon weapon 32.5 inches long, with its blade largely intact and with five silver bands around the hilt. The sword was found near the old ford at Gilling bridge in 1976, doubtless having been dredged up from its peat bed during re-grading of the beck.

In mediaeval times, and until comparatively recently, the parish of Gilling extended far beyond its present boundaries. In 1233 the Pope licensed the archbishop of York to build chapels in outlying places to be served by curates paid by the vicar. The necessity for such 'chapels of ease' was especially felt in Yorkshire, where a great many people might be cut off from their parish church in winter by flooded rivers and impassable roads. The archives of the see of York show that in 1344 'the abbey of St. Mary's possessed the church of Gilling with the chapels dependent thereon', and the abbey register for 1309 gives those chapels as Barton St. Mary's, Eriom (Eryholme), Cowton, Forcett, Hutton Magna, Appleby-on-Tees (Eppleby), Barford-on-Tees and Mortham. Already in the 15th century Mortham lay waste, and St. Lawrence, Barford, just south of Gainford, has long been a total ruin, but a report of the Charity Commissioners in 1548 in respect of Gilling could still speak of 'six prestes belonging to the sayd paryshe at the findyng of the vacare there, besides the two chauntrye prestes'. Parish returns in 1783 and later years show 'annual immemorial payments' made out of the vicar's income to the curates of Forcett, Hutton Magna, Barton St. Mary's and Cowton. These places, with Eppleby, Eryholme and parts of Stapleton, are marked 'Gilling (detached)' on the first of the six-inch Ordnance Survey maps of the district, published in 1857. But although the vicar of Gilling is still a patron of the churches at Hutton Magna, South Cowton and Eryholme, all dependent chapelries of the ancient parish were designated vicarages by the late 19th century, having been declared independent benefices following the Pluralities Act of 1838.

A stroll through Gilling http://www.northyorks.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=355&p=0

From the 9th century, Gillingshire was ruled by Anton's ancestors, the Earls of Mercia.

Lady Godiva was the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia.